“Awake, brothers! We are attacked! To arms, and the devil take the hindmost!”

There must be no wavering when the call to arms erupts amid the sleeping tents.

To wake out of sleep and handle a nightmare situation is the goal of every soldier’s training. In the instant switch from individual dreaming to unthinking member of a survival machine, the human moves from 0-60, biochemically speaking. The sudden flood of cortisol shocks the body into high gear, testing its capacity to deal with imminent danger. And if as a soldier your fight/flight mode cannot trigger instantly, that millisecond’s delay may curtail your very life and that of your fellows.

But how to program this blind esprit de corps into modern young men in a nominally free society? The industrial American military of the 20th century built and maintained good order by drilling former civilians into reacting automatically to alarms. The sought-after result: the soldier’s strong, immediate duty reflex. All selfish thoughts extinguished, he greets the interruption with, “I will rise and not think twice, performing my function directly and well. I will follow the orders of my commanding officer and my beloved corps.”

There is a scene from Full Metal Jacket that depicts this disruptive reveille of recruits in the middle of the night. The drill sergeant wakes them into an instant nightmare. Notice how efficiently the young men’s choices are twisted into subjugation to the leader’s will. By 1967, when the scene is set, America has a well-oiled machine to turn its young men into killers.

An exceptional Illinois product of that industrialized military training was Naperville native Robert J. Wehrli, who in 1945 led his PT Boat squadron in a close-range attack against a Japanese hideout in Batangas Bay, Luzon, in the Philippines. His Silver Star citation reads, in part: “Undaunted by intense automatic fire from the enemy shore guns … [and] [a]lthough his boats received numerous hits, [Wherli] succeeded in burning and destroying [the] Japanese installations.”

Being shot at did not fluster Commander Wehrli. The Marines and his athletic background (All-American in 1939 at the U of I under legendary coach Robert Zuppke) had programmed his mind and body to methodically act with violence and without thought of personal safety.

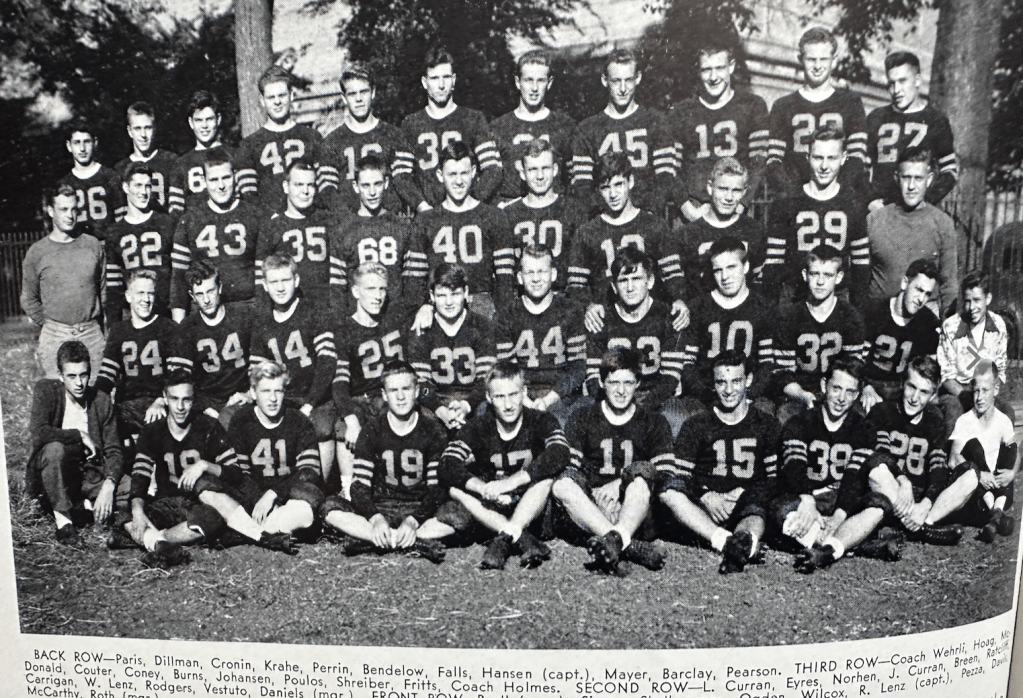

When he returned to civilization, this decorated killer found employment at Oak Park and River Forest High School. There he coached the football team through its most glorious era into the 1950s. Wehrli drilled his boys with the same sort of Jap ass-kicking energy that had turned the tide at Guadalcanal and won him his star. In the immediate post-war years, his squads won West Suburban championships and achieved perfect, undefeated seasons in 1947 and 1948.

Fast forward thirty years, and Wherli is no longer a coach, but chairman of the Physical Education department. He is in his last year but still a martinet who stalks the gyms and locker rooms.

“On your feet! Get out of there on the double!”

The bark shocks me out of my dreams and propels me up and out of the towel station, a little enclosure between two banks of showers in the boy’s locker room: the locker room I was supposed to be monitoring.

Instead, I have been napping on soft stacks of towels in the dark booth. Unknown to my supervisor, I am feeling extra tired from Elevil, the tricyclic antidepressant I’ve been prescribed. My 15-year-old body feels especially drowsy this day.

“Just what do you think you’re doing in there?” His eyes narrow upon me.

“N-n-napping, sir,” I stammer. For the man intimidates me. He has found me out, and my head feels woozy. This is no ordinary coach calling me to account. This is the Head Coach of head coaches, the Chairman of the PE Department, the man whose trophies and team photos are proudly displayed in the Monogram Room. And who am I, a mere second-string sophomore trying to avoid study hall?

“Napping!” his shout echoes off the shower tiles. “You are derelict of duty, young man. What’s your name?”

“B- Bendelow, sir.”

If he connects my unusual last name with his starting end on the 1947 and 48 championship teams, he doesn’t show it.

“You should be out here, watching!” He points his beefy hand to the adjacent locker room. “Your job is to make sure no one comes in and messes with the lockers, didn’t you know that?” There is scorn in the question.

“Yes, sir.”

He sighs, exasperated. After thirty years in the system, he knows how inescapable entropic dysfunction is. He accepts my weakness. But he cannot let me off easy. And perhaps he also recalls my father’s solid play on both sides of the ball.

“Why, in the military,” he tells me, “if a man fell asleep when he should have been watching, do you know what they do to him?”

“No, sir.”

“He was shot!” And he pauses, letting his loud, husky voice ricochet around the showers again.

The coach lets me off with this warning, but the episode affords me a glimpse into my father’s training, the standard male programming of mid-century America. Coach Wherli, the oldest of 13 children, was disciplined as a boy into our national sport of organized violence (“America’s Game,” the NFL is called). He was all-prep at Naperville Central, then All-American at Illinois. The Marines apotheosized his skills into glorious mortal violence in the Pacific war. He was a star, earned his star, and then set about trying to create stars in his teams, which included my father, who learned warrior readiness from him.

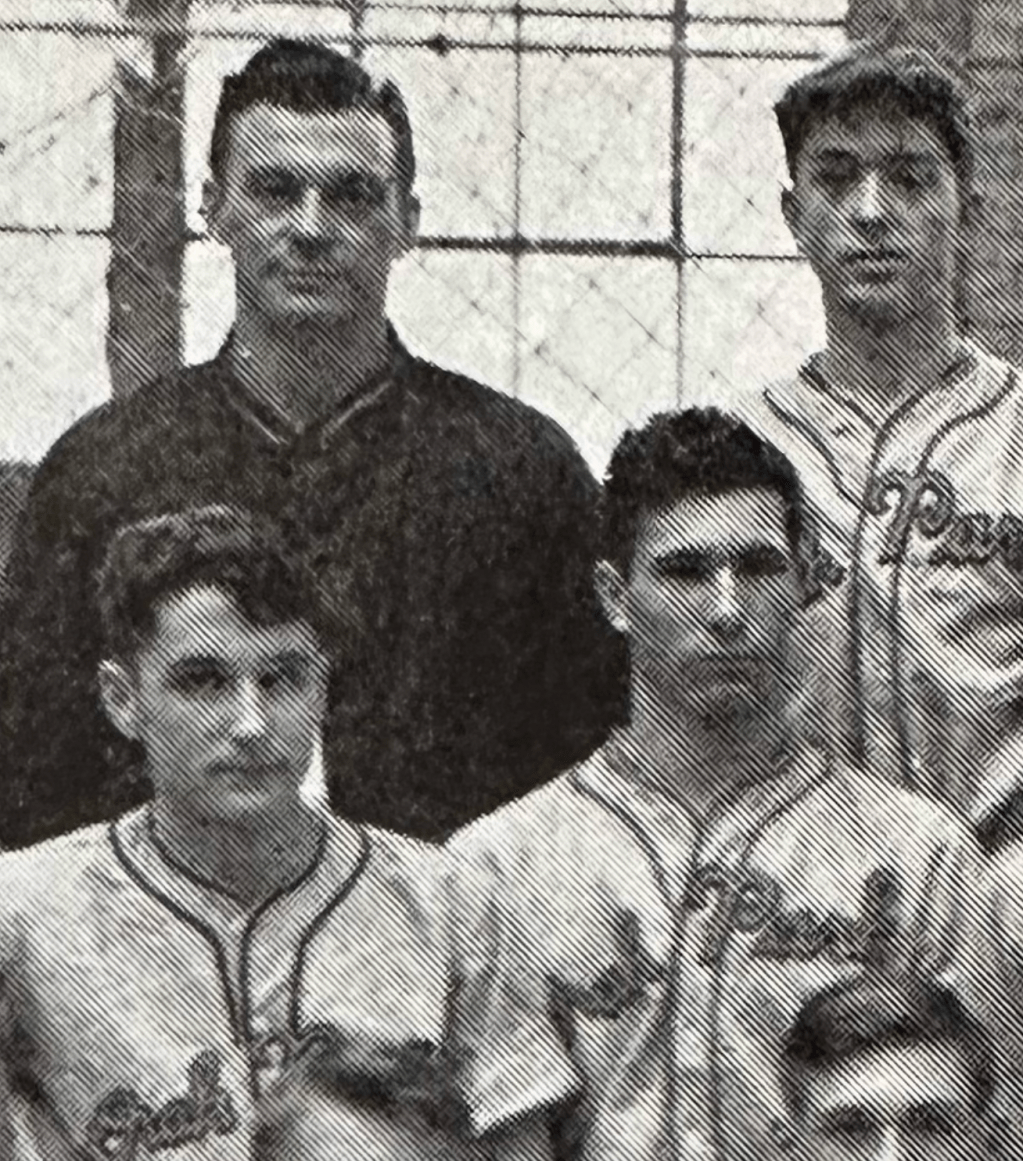

Coach Wherli was also dad’s baseball coach. Here they are right next to each other in 1948:

To be able to wake out of sleep and into a nightmare fight, to kill without question, to persist in self-sacrifice until victory, this is the spirit of the man at war, his ego subjugated to superiors, a citizen in temporary slave mode.

One night when I was 10 I sleepwalked: I got out of bed while sleeping when a dream ordered me up to fulfill an urgent duty. I dreamt I was playing baseball where I wasn’t supposed to be, and with a willful swing of my bat, my ball broke a large plate glass window that I would now certainly have to pay for. The window cost at least fifty dollars, and my parents weren’t wealthy. So I had to march, I had to do my duty.

Dream logic commanded me to march like a soldier on guard, from one end of my bedroom to the other and then back again. The dream told me that each time I completed the assigned path, I got a dollar. So I counted aloud. “3…4…5…”

My bedroom was adjacent to Sheila and Sarah’s room, and the noise of my compulsive pacing awakened them. They alerted the commanding officer, Dad. I suppose he came and gently took me in his arms, because I recall being awakened there out of my illusory duty dance, and returned to a comprehending state. “Thanks, Dad!” His kind reception delivered me from feeling alone and overwhelmed with obligation in my dream.

Around this time in my life, I am regularly having vivid dreams, inspired, no doubt, by the large amounts of testosterone my body produces. Exercise enhances these amounts. These dreams lead, not merely to nocturnal emissions, but on occasion to terrifying nightmares that trigger my brain into fight/flight/freeze mode.

In one particular dream, I am asleep in my room at night when a noise in the house awakens me. I understand that I am alone–no one else is in the house. I immediately assume the role of hero/defender of the property. I see the shadowy intruder moving through the rooms, and with my father’s shotgun in my hands, stalk him until he begins to pick things up. That’s when I hit him with a righteous blast from the gun. He dies instantly as bad guys do on TV cop shows.

In my dream I feel proud, satisfied that I’ve passed a manhood test in keeping my home safe. But then I approach the dead man and take a good look at his face. He’s swarthy, bearded, unknown to me, but with growing horror, I notice that his visage has seams. The mysterious intruder has artfully concealed his real face with a mask. I lift it and am astonished. Under the beard and alien pallor, the man I had been so proud of killing is none other than my beloved father. His blood is on my hands.

My horror and shock are Oedipal, vast, subterranean. I am terrified to see Dad as never before, as my opponent, my rival, a man whose strengths I must overcome to become a man myself.

I wake profoundly shaken by this dream, cast down by its revelation, stumbling into the sudden nightmare of day dawning, and I, a virtual parricide. I gaze hereafter through a jaundiced lens. Guilt colors my self-esteem for a long time to come.

Still another waking into real-life nightmare occurs when I am 16. The Scoville house has neither mother–she’s moved into her own place–nor older sisters–Sharon and Sue have moved into their adult lives. Left are just us “lost children,”,my older sister Sheila, younger sister Sarah, and I. It is 1977, and punk rock is sweeping the UK.

In Oak Park, Illinois, through an unsought divorce and business failure, my Dad is a beaten man, his athletic frame now encased in layers of fat, which also coat his internal organs.

What has weakened and bloated him is not something external, but his choice of vodka as painkiller. Now when I see him wobble in his formerly smooth stride, I know he has been turning his Tab into a cocktail, and that he is weak. He may have a hundred pounds, a few inches, and thirty years of embattled experience on me, but my body knows: my opponent is weak.

On this occasion, I lie on my bed reading Hamlet and see his unsteady form looming outside my bedroom door. Then I hear his tired voice repeat what I (and I think down deep he, too) knows are false accusations regarding something I’d said to or done to one of my sisters in a recent conflict.

“So, you need to apologize to her,” his voice is tired.

I snap.

All the repressed energy of a boy who’s been weight-training and looking up to Arnold Schwarzenegger, and his coaches, who’s finally given up trying to connect on a deeper level with his father, and who can no longer tolerate the injustice of it all, erupts on dear old Dad.

I am instantly in his face, shouting defiantly. “I. Said. NO. such. Thing!” I punctuate my words with jabs at his shoulders, a provoking gesture. He reaches up, as I knew he would. With his large arms, he intends to manhandle me.

But my body grabs and gathers his soft frame first. He is off balance and I push him easily onto the floor. Quickly, I straddle his torso, my knees pinning his once-mighty shoulders. My fists are balled, ready to break his reddened face, when, from his spittle-flecked lips, a smile beams. He pants, and grunts, “Heh-heh– now you can beat up your old man, right?”

And I, panting myself, am suddenly struck by the deep wrongness of this situation. I have never before openly rebelled or defied him. I love and admire him. And here I am, ready to kill him.

The child in me jumps off him, feeling suddenly submerged in garments too large, not ready for the enormous strength I now own in my body. I stand back into my room, and watch as he gets up jerkily to his feet, and then staggers out. “Ah!” he waves his hand dismissively in my direction, as though I am not worth the rebuke, “for the love of Pete!”

He would fight me no longer.

From this day on he avoids me, and when we’re together is cooler towards me. He knows he has the moral high ground, knows that in my mind, I am no better than Oedipus, Lizzie Borden or Charles Whitman. I am he who would defile generations to come and bring pestilence to my fellows, being the most polluted.

A self-horror emerges. I can no longer deny my violent inclinations, no more than when I tormented my sisters, nor when I fantasized about murdering the class guinea pig by enclosing her in a glass jar and dropping her onto the concrete three floors below. I wanted to awaken her into a nightmare of my own devising.

Yes. In this violent male world, my father and I are one.

Leave a comment