He served in the Korean War with the Marines, but a veil lies over my father’s actual service, and he gives nothing solid in reply to, “What did you do in the war, daddy?

My oldest siblings, Sue and Sharon, recall his telling them, “I did a lot of typing,” which is plausible, my dad being a college boy caught in the draft with strong language skills.

And he ended up a Staff Sergeant, to whom clerical duties are given behind the lines.

But he also was close friends with killers like his decorated hunting buddy DeVore, who was awarded medals for shooting scores of Chinese soldiers around his almost overrun machine gun position.

So we know dad was in a unit that saw combat.

Though the service only took two years of his life, it marks his notions of propriety for the remainder of his days and nights.

You can see it in his stubborn conservative values, his disdain of hippies, and the firmness of his grasp on his parents’ and grandparents’ values–faith and family first, then hard work, and then, finally, hard play–play with a violent edge preferably. Baseball and 16-inch are fine, but hitting people, essential in hockey and football, are his main attractions, and absorb his energies when a young man. He relishes the rough and tumble, and after his time playing end at the University of Tulsa, he becomes a football strategist, always seeking higher intelligence of the enemy’s movements, the better to destroy him. Like a memoir writer, he takes his point of view from the endzone, where he can study the opposing team’s weaknesses.

When my younger sister Sarah and I ask him later, he allows, “I shot at people and didn’t look back.” And then he changes the subject.

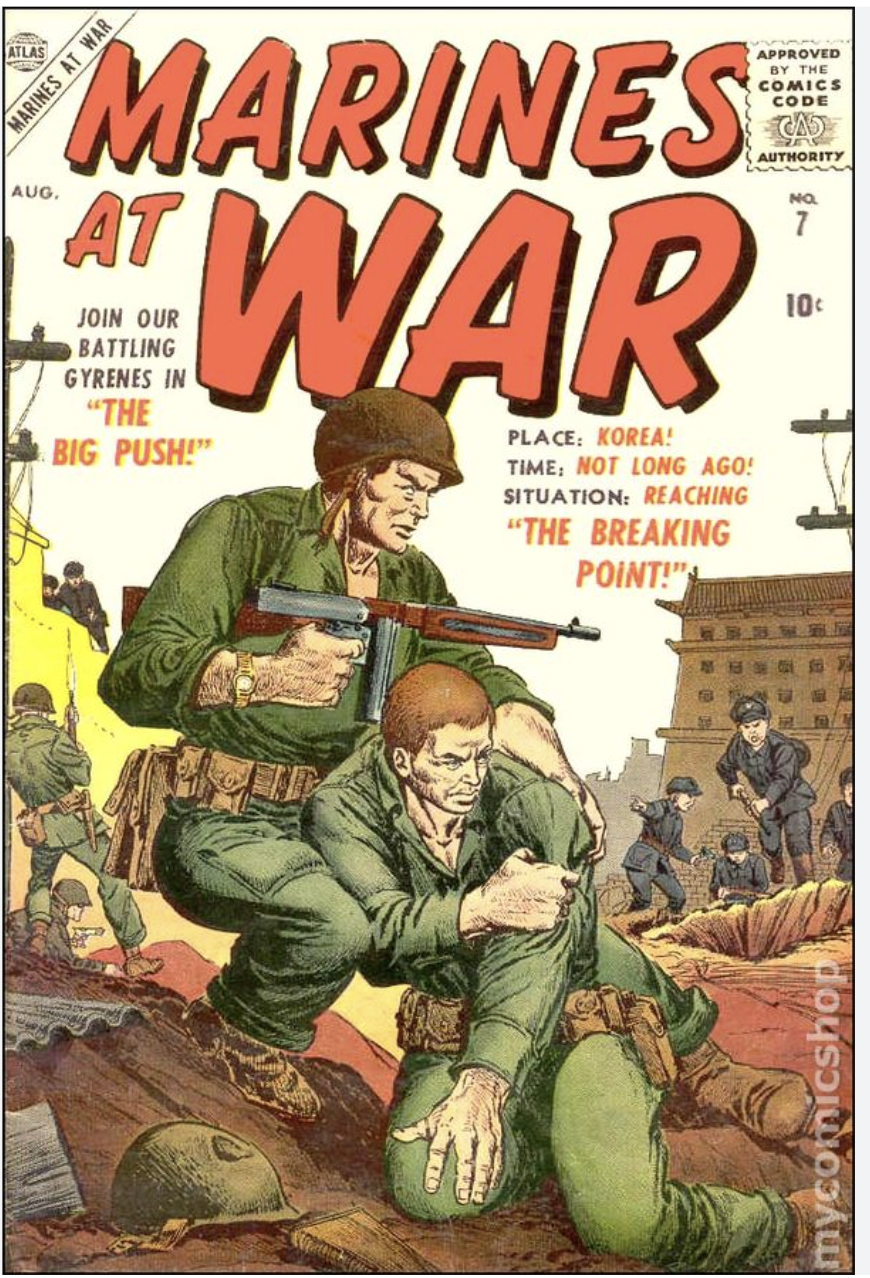

Like many boys of my generation, I am fascinated by weapons and war stories like Marines at War. But dad maintains a defensive perimeter around the topic. The more he puts me off, the more I want to know. “What is so horrible that he cannot speak of it? What orders must he have followed and now regrets beyond words?”

He defeats all my attempts to learn more. Nor does he want to watch on TV what my ten-year old mind believes the height of exciting film-making: The Sands of Iwo Jima, starring John Wayne. I am disappointed. Dad has been a Marine at war, and he now has no interest in the subject. In his mind, he wants to leave those days behind.

In a moldering canvas bag in the back of the basement I find random pieces of his war-making attire: rabbit-fur lined shooting mittens with trigger finger extensions, a khaki uniform with red sergeant stripes, an aluminum canteen. He has abandoned them along with an old-fashioned ball glove and a deflated game ball he won in some forgotten football victory.

His fighting spirit, too, seems spent. He meekly endures business setbacks and his wife’s scornful abuse with silent, seeming acquiescence. Some nights, when she has the energy, she climbs up out of her sedation and screams in rage at my soft-spoken dad, and.everyone’s sleep is disrupted. “You useless asshole! I hate the fucking sight of you! You’ve ruined my life!” And then the sound of her fists striking his torso, but never a shot in defense from our veteran dad.

When I am nine and my sisters and I are asleep in our rooms in the wee small hours of a school night, my dad is twenty years into his tortuous marriage. This is when his inner Marine unexpectedly comes out.

His loud, urgent voice startles us awake. “Alright, you lousy kids! Out of bed, now! Downstairs, now!” His face is set in icy earnest, his dark eyes shine. The change in appearance shocks me. Where is soft-spoken dad? What is this drill sergeant’s bark coming from his throat?

Assembled downstairs in the living room, standing straight in front of our couch, my older sisters are whimpering and shaking quietly, tears on their faces. Sarah and I exchange a nervous smile. This is so strange! Where is this going?

He barks at us about our lack of discipline. “You kids are going to listen to me, and do as I say, and it’s going to be as I say, or there will be punishment!”

He has us do exercises–jumping jacks, pushups–and though it’s unclear why he’s doing this, he is in extreme earnest. He threatens that if we don’t do as he says, we will clean the basement floor with a toothbrush, “like they made us do in the Marines!”

At some point, my sister’s whimpers and the sobering effect of his exertions move him to dismiss us back to our beds. We separately retire from this strange little nightmare back to our rooms, with no understanding of what has just occurred.

Neither, the next day, is there acknowledgement of the previous night’s drill session. None of us, neither his perplexed children, nor the now less-trusted parent, speaks of the event.

Perhaps it was a dream. It seems wrong and shameful to speak of it, somehow. Yes, easier to forget as a bad dream. Perhaps war stories are like this, forgotten by mutual consent.

I now believe that our stoical father, usually neutral or kind to us, had been driven temporarily out of his mind by the extremity of his situation. His brain, programmed by team sports and the Marines, knew to solve chaos and disorder through strict discipline. And since he could not discipline his alcohol and pill-addicted spouse, he turned to their unruly offspring, and for a brief moment found some release from his chaos.

Leave a comment