Dear little “me,” age 11,

Let me tell you what I know about your fantasies, young man. And do not redden with embarrassment. It is I, your loving parent writing, and whatever truths I tell come from a compassionate analysis of your mind’’s images. For you are not responsible for your fantasies. They arise by themselves in our minds, all on their own.

Let’s start with an easy fantasy, your football fantasy. Dad felt safe with you around his favorite sports. In the car or backyard, you’d listen together to Jack Brickhouse and Irv Kupcinet’s home team call on WGN and you’d see his mood change in response to the game. When you were an impressionable seven years old, on a few peaceful Sundays, dad invited you up onto his and mom’s bed facing the 20 inch black and white TV. He leaned back on pillows, nursing a Tab soda in a green glass, munching some salty Bugles and watching his beloved Chicago Bears.

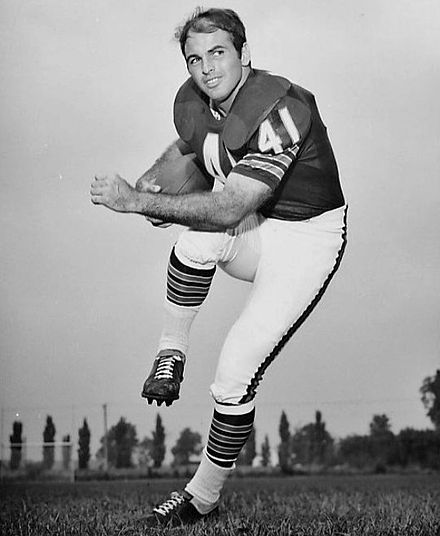

You saw clearly that In the entire game of American Football, nothing triggered dad’s delight like a breakaway play by the most explosive players on the field: the running backs.

The game-changing running backs of 1969–Brian Piccolo, Ronnie Bull, and especially Gayle Sayers–you saw clearly were the best players on this team, the ones who got instant appreciation from every fan in Wrigley Field, the announcers, the rest of the Bears, and fans like your father, whose joy fascinated you. Nothing launched dad’s body up and off the pillows, or tore loud cries from his lungs like a solid gain of ten or more yards.

So it was no surprise when you finally got to join PeeWees and put on pads three years ago, you told the coach you would be a running back, the ones who broke free and brought happiness.

Your fantasies powered your practice. During handoff and footwork drills, stiff-arming the dummies, or running sprints, in your mind you were evading capture for a noble cause, fending off defenders and racing to the end zone with everyone’s hopes clutched in your hands.

In typical scrimmages and games that season, your bones got crushed under a pile of bigger boys, sometimes knocking air out of your lungs, a little presentiment of death. But once or twice your fantasies got realized, at least somewhat. You broke free from the line and ran 40 yards for a score in a game at Barrie Park. And sure enough, with the ref’s whistle and upthrust arms came the hoped for outpouring of applause and shouts of adulation. At you alone. The universal affection flooded your brain with dopamine. And you wanted more of this running back feedback, please.

But your half-and full back dreams were cut short next season, when the coach told you were a running back no more. The team needed you at quarterback. You got to “lead” the offense, but the freedom your fantasies gave was impossible. Instead of free flight, you were stuck under center, calling the cadence and taking snaps. Alas, from then on, through high school and for the rest of your life, you never made a long run for a touchdown again.

As you get older, you’ll see how fantasies change with the situation, but your football dreams reanimated in me yesterday as I ran my backyard obstacle course. Your future body, in its 62nd year, imagined itself evading the outstretched hands–not of linebacker Ray Nitschke–but of too-swift entropy and avoidable disease. It high-stepped over old thinking and broke free into an open field of what seems limitless possibility.

“You” are still running, little man. But your goal has altered. I fantasize now about getting into the end zone of death and scoring the touchdown of a satisfied mind.

Leave a comment