In 1974, my friend Karen Frerichs was a 12 year old playing by herself outside her family home in Kankakee. A crop dusting plane coated the adjacent field with pesticide, but it wafted over to Karen on a breeze. Her eye membranes, which absorb pesticides faster than any external body part, took in the toxin, and the next day she permanently lost her vision.

Sandra Steingraber had been a healthy 20 year old when she contracted deadly bladder cancer along with a cluster of people near her Tazewell County home. The most likely cause: drinking, cooking, and bathing in water polluted by the 54 million pounds of pesticides Illinois doses its crops with each year. By the time she is my college classmate in 1982, Sandra has fought her cancer into remission and is planning a graduate degree.

Summer 1986: I work as a house cleaner to cover expenses between adjunct teaching jobs. One day, in a Lincoln Park bathroom, I am up against stubborn residue on a shower surround. When my employer-supplied bleach-based product fails to work, I reach into the company bag and try a second. Unfortunately, it is ammonia-based, so a cloud of toxic chloramine gas fills the air. Inhaling it knocks me down, and I have to crawl into the hall to regain my breath. I vent the bathroom and finish as best I can.

In the hours after this poisoning, I realize how lucky I am to have only a lingering headache. I also feel angry, like Karen and Sandra, at the institutional practices that have just insulted my body.

I vow to find a better way to clean, and in the weeks that follow, I do.

Out of my need for money, my joy in cleaning, and my anger at dangerous, inhumane methods, I start Chicago’s environmentally-safe maid and janitorial service, ecocleaning. Anita Roddick, the founder of The Body Shop, is my role-model: her store “green-ed” the market for a basic commodity, beauty products. She had to source earth-friendly ingredients and charge higher prices, but she gave customers value added, a quality product in line with their values.

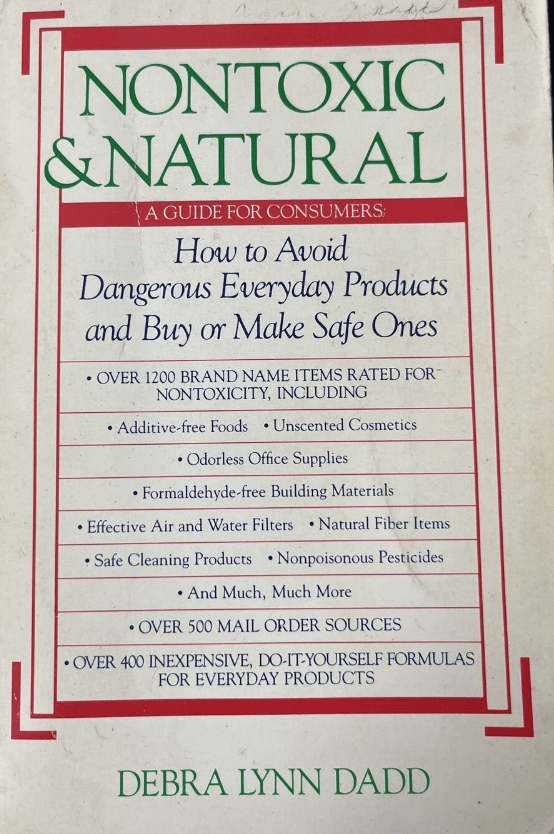

My goal is to do the same for home and office cleaning. One of our first epithets is “the greener cleaners.” I supplement ideas from Debra Lynn Dadd’s Non-toxic and Natural (1984) with my own research into pre-detergent era methods. We use HEPA filter Miele vacs and curated cleaning supplies. With a few well-placed ads (the Reader, Outlines, and Windy City Times), we attract clients in Hyde Park, Evanston, and Oak Park.

Our tagline, “Clean home, clean conscience,” does not appeal to a majority in Ronald Reagan’s America. But along Chicago’s lakefront is a thoughtful client base of artists, activists, therapists, yoga studios, and high-end catering kitchens ready to take a chance on my venture. Within two years, our profits are growing steadily. Going green has brought me and my family some needed green.

However, I discover serious downsides to running a flourishing new business by yourself. My workload balloons to 60-70 hours a week during the school year. Especially after my kids start arriving in 1989, I am home not nearly as much as I’d like.

Additionally, because maids enjoy privileged glimpses into their clients’ lives, clients demand more responsiveness than they do with, say, their lawn service. Stuck school days in classrooms, I am obliged to stay tethered to the best available technology for keeping in touch: my answering machine. I am unable to respond to real-time customer messaging and emergencies. And I am thus distracted from what should be a teacher’s sole focus: his students and their progress.

I fail to get a partner to help manage my team of 8-12 ecocleaners. My strongest workers have no interest in more responsibility. So over the next few years, I stop advertising the maid service and shed home customers down to a core group of happy, established accounts. I steer ecocleaning toward the much more manageable waters of janitorial service and office cleaning because, as the main financial support for a growing family, I cannot afford not being entrepreneurial.

After school I drive my 1987 Ford Festiva around Chicago to supervise cleaning jobs like the Greenpeace offices in the west Loop, or Gourmet Affairs, a catering kitchen in Ukrainian Village. Both are busy workplaces needing intensive cleaning at the end of shifts. One of the filthiest places ecocleaning ever tackles, ironically, is the “smoking lounge” at Greenpeace where canvassers for a cleaner world puff heavy pollution into their lungs and onto every surface of this never-empty lounge. The room smells and looks like a big ashtray.

In the years we clean Gourmet Affairs, regular operations are punctuated by immense celebrity affairs like huge dinners the Pritzker family hosts. For me, a tv-raised man who has never felt near the center of things, it feels cool being even adjacent to famous people.

Being the only business of its kind in Chicago, ecocleaning gets hired by Lakefront Liberals and progressives to signal their virtue to whoever is paying attention. Accounts like the Center for Neighborhood Technology, and later, the well-connected PR firm Jasculca & Terman come to us this way. We are a desirable value add to office cleaning. Even some hedge funds and arbitrageurs “greenwash” their brand with us.

We won’t keep these accounts, though, if our work isn’t of high quality. But I am up to the challenge. My deep enjoyment of cleaning is well-documented elsewhere, so it will come as no surprise that I relish meeting and surpassing client expectations. My enthusiasm rubs off on my best workers, who stay ecocleaners, year after year.

Quite the opposite of the poison cleaning that started me on this road, I find ecocleaning healthy for me. It involves purposeful activity, intellectual stimulation, light aerobic exercise, and weight lifting at the end of days spent cooped-up in class.

I also enjoy the same meditative peace I’ve always experienced in cleaning flows: alongside workers and sometimes alone, I empty trash, break down boxes, wash dishes and pans, and even clean grease traps.

Leave a comment